by William Wayland

Studio to Stage is a series that explores how music is made in the Bay Area. We follow local artists from the recording of their next single, EP, or LP to the release show at a Bay Area music venue.

The following interview has been edited for clarity.

William Wayland: Alright. Let’s get into it. So, Greg, what inspired your new album, Hit Music?

Greg Hoy: I was dealing with some back issues last summer—neuropathy. Basically, I have two compressed vertebrae at the top of my neck, and the next three have bone spurs and arthritis. So when I was playing guitar—especially standing—my left hand and arm would go numb. I discovered that on tour.

WW: I think you told me you noticed it first in Berlin?

GH: No, Berlin, the club in New York. It happened there. Ironically, I had just been talking about Steve Albini that week—he had just passed away—and I had this numbness in my arm. I wondered if it was psychosomatic, but no, it turned out to be real.

So, as part of rehab, I had to keep those muscles moving and I had a little space at The Old Croft in Pacifica with a drum kit, and I basically taught myself to play drums again. I’d go in every day or two and just play along with stuff—Phil Collins, Fugazi, the Mad Men theme. I did tempo work with drum and bass tracks, like Grooverider and Public Enemy. It helped loosen things up, even though it hurt.

Eventually, I started writing drum parts—and they became the foundation for the songs on the album. Instead of starting with guitar or melody, it was drums first, then bass, then guitar. Totally backwards for me.

WW: As a guitarist, that must’ve been a big shift, right?

GH: It really was. And it ended up being a fresh way to work. There’s something about picking up an instrument you’re not super confident in—it frees you from worrying about what’s “right” or “wrong.”

WW: You kind of trick your brain into being more experimental?

GH: Exactly. I did that for about five or six months, just recording random stuff. And then eventually I had a handful of songs.

WW: And, I know that a sign outside Vallemar Station in Pacifical influenced you, too?

GH: Right. Around the same time, I was driving past that “HIT MUSIC” sign outside Vallemar Station every day on the way to the studio and thought, that would make a cool album cover.

That led to the idea: What if I made a record that wasn’t a greatest hits album, but felt like one? Like, what if I said, “Here are 12 of the best songs I’ve ever written”—not linked by genre or mood, but just by strength. That freed me up to experiment more—like writing and arranging actual horn parts for the first time.

WW: So you wrote the horn parts yourself?

GH: Yeah! I found this amazing trumpet and trombone player online–Kelly O’Donohue. She was living in Germany at the time.

I made videos of myself singing the horn lines—like, “bap-BAHH”—and sent them to her. And she just nailed it. We never even talked on the phone, just emailed and shared videos back and forth.

And what was great about working with her was that she just got it. She was intuitive. I’d seen her previous work, and I could tell she moved fast, which is how I like to work. I don’t like a lot of back and forth or confusion in the process.

I also had Ben Opie. He played sax on “The Simulation”. Ben is an incredibly underknown Pittsburgh-based jazz cat.

WW: You’ve written so many songs and albums, do you even know how many records you’ve made at this point?

GH: My lawyer and I were just going through my catalog for publishing stuff. I’ve got around 600 songs registered now.

WW: 600! That seems like a lot.

GH: And that’s not just singer-songwriter stuff. I did a lot of instrumental and electronic work back in my New York days—some of it ended up in commercials for American Express and an episode of One Tree Hill and others.

My PR person in Jersey said this is my 16th record or EP, depending on whether it’s under Greg Hoy or Greg Hoy & The Boys. I’ve had other project names too, but yeah—my first real solo record came out in 2003. So that’s 22 years now.

The original goal was one record a year. Some years I’ve done two, or an album and a couple EPs. When I moved to San Francisco, I started working out of Tiny Telephone in Oakland—John Vanderslice’s studio. He had this crazy deal at the time to help fund the space, like a few hundred bucks a day, so I’d just book time even if I didn’t have anything written yet. My drummer Jason Slota would show up, and I’d write songs on the fly. I didn’t even have anything written.A lot of that stuff sat on hard drives for years—but when I needed a filler or spark, I’d dig into those sessions.

I look at making records the way some people look at baking brownies. Sometimes I just record to record. This record is kind of different because it became very structured and succinct at a certain point. But I still have probably 30 songs sitting on this external drive that are pretty much done, that I haven’t let out into the world. They may never be let out into the world.

I just love it, you know, I just love recording. I love arranging. I love mixing. I love all the things that I think a lot of musicians dislike. I like to record as fast as possible, and then spend hours tweaking stuff and making it sit together.

I come from that 90s DIY punk era. Back then, when you made a record, you’d probably go into a proper studio—but everything else you did yourself. You did the artwork, you dubbed the cassettes. I remember sitting around with the band copying tapes by hand.

Now, you can do everything on a half-pound laptop. I’m not sure younger musicians always grasp what a miracle that is. It used to take these giant rooms full of electronic gear to get the kinds of sounds we can now make instantly on a screen.

I’ve always loved doing it yourself. In college, I had a four-track cassette recorder, and I’d record everyone I could. The acoustic singer-songwriter dude down the hall, this beautiful singer I worked with—we’d set up mics and try to get the best sound possible. That hands-on spirit stuck with me. And I think, for musicians today—especially those writing regularly, which seems like the pace now—you should also be recording your own work. Even if it’s just on your phone. There’s something powerful in that immediate playback, that instant analysis.

And it’s so easy to share your work. Of course, sharing doesn’t guarantee anyone will listen, but there’s no longer a barrier. You can drop a track on Bandcamp, upload a video to YouTube—it’s all right there.

I think the word I always come back to in these conversations is craft. What’s your intention? What’s your technique? How are you refining it? Craft applies to anything—whether you’re building a chair, writing a poem, or making coffee. It’s about consistently modifying, improving, trying new things. And I tell younger musicians all the time: you don’t have to put the first thing you record online. Or the 100th thing. You are your first audience. I’ve probably listened to each of my own records hundreds of times before they ever go out. By the time I get the vinyl test pressing, I try to listen like a fan. And if I’ve done everything right up to that point, there are no surprises. That’s where the joy comes in.

One of my favorite bands is Guided by Voices. Bob Pollard has probably released 20,000 songs. He puts out everything. I think he even said once that he writes songs while sitting on the toilet—and releases those, too. And he has an audience for that. But I think with how saturated things are now, you owe it to people to make it worth their attention.

WW: That would be like taking thousands of photos a day and just saying, “Here you go.”

GH: Yeah, and I think that was a particular moment in time, too—the peak of the lo-fi movement, right when digital tools were starting to take off in the early 2000s. I still love recording to tape. There’s something about the aesthetic and the feel. But there was that shift—I’m sure you remember—around 10 or 15 years ago when all these kids started buying film cameras again. Polaroids, Hasselblads, 35mm. I think what they were missing is exactly what we’re talking about: this idea of getting it right before you hit the button. That’s the craft.

For this new record, I recorded really quickly—but I did full takes. I didn’t want to be copy-pasting loops or stitching together bits and pieces. I wanted to play it as if I were part of a four- or five-piece band, capturing a full live take. So that meant I had to do the work before I hit record. That’s the point I try to make: record, yes. Create, yes. But get to a place where your gear is just capturing a moment—not manufacturing one.

WW: Tracks like “Yep,” “The Simulation,” and “What My People?” comment on modern technological realities. What are you trying to say in those songs?

GH: I grew up reading science fiction—Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Alien, 2001: A Space Odyssey—and I’ve always had a healthy distrust of sentient tech. In those stories, technology is supposed to help us, but there’s always this coldness, this non-human aspect. HAL 9000. Ash from Alien.

I’ve spent 15 years working in tech, always on the people side. And what I’m seeing lately is the human element getting pushed aside—marginalized—by algorithms and data-driven decisions. It’s not always in our best interest.

That’s what was in my head writing those songs. “The Simulation,” for example—if you’re spending hours a day on your phone, or online, or even just watching TV—you are in a simulation. That’s not life. That’s not reality. Life is when you go to Muir Woods, or Yellowstone, or a state park, and you just look at stuff with your eyes. You feel the oxygen on your face. You don’t pull out your phone to document it. You just are. That’s being human.

That’s something I’ve come to realize more in recent years: I want to use whatever voice I have to remind people of that. So those lyrics—they’re my way of saying, “Yeah, you’re online, and that’s okay. But don’t forget—it’s not real. Even a picture of you isn’t you. It’s just a picture.”

WW: That’s interesting, because I’ve got my phone right here. I can pick it up, read the messages, and I would’ve told you, “Well, no, that’s not really an alternate reality. This is physical—I’m holding it.” But the way you’re putting it makes me think. Because you do get naturally lost in your phone. If I open a social media app—

GH: Not to interrupt, but I gotta say—I wouldn’t call that “naturally” lost. You’re purposely lost in that phone.

Like, knowing the people who made these phones… I interviewed the designer who came up with infinite scroll. He regrets it now. But someone was gonna do it.

WW: I consider myself pretty good at putting the phone down when I want to, but if I’m honest, how many times does infinite scroll get me? I’m watching a funny dog video, and then—bam—another one pops up. And then another. And the next thing I know, it’s 3:30 in the morning.

GH: Exactly. And listen, William, you and I remember a time before any of this existed. The new generations coming up? They’re growing up in it. The human and the machine are already so intertwined—it’s only going to become more and more like that. I don’t know that it’s a good thing. I think we’ve got to be healthy about it. Be aware.

WW: People are going to look back on this interview and say, “Those guys were onto something. Greg Hoy—he was onto something.”

GH: [Laughs] If the robots let it exist.

WW: Right? I want to ask you about the video for “What, My People?” How did you get the aliens for the video?

GH: [Laughs] I ordered an alien mask off Amazon.

WW: That wasn’t real?

GH: Nope. Just me. It’s all me. I shot it in iMovie with a green screen.

WW: I couldn’t tell. I thought maybe you had two other people in there with you.

GH: Nope. Just me. That’s the magic of it. You can sit down in an afternoon and make a two-and-a-half-minute little mini-movie. And that’s wonderful. And special. And I’m so grateful for that. But then the question becomes—what are we going to do with this? With this kind of tech?

The whole idea for the video came from those weird UFO stories in New Jersey toward the end of last year. And I was like—okay, what if aliens landed? But instead of sucking out our souls or probing us, they were like, “Hey! Let’s rock.” You know? Of all the things humanity’s doing to itself, rock and roll is still the coolest. So that’s what they’d want to do.

WW: [Laughs] I love that.

GH: So at the end of the video, when the two aliens find the Marshall stack—it’s kind of like 2001: A Space Odyssey, with the monkeys and the monolith? That’s the vibe. That would be my hope: if another lifeform landed here, they’d find the good stuff.

WW: Okay, with Hit Music marking your—what did we say, your 16th LP . . .

GH: Yep . . .

WW: How do you envision progressing from here? Are there new genres or collaborations you’re interested in exploring? What’s next?

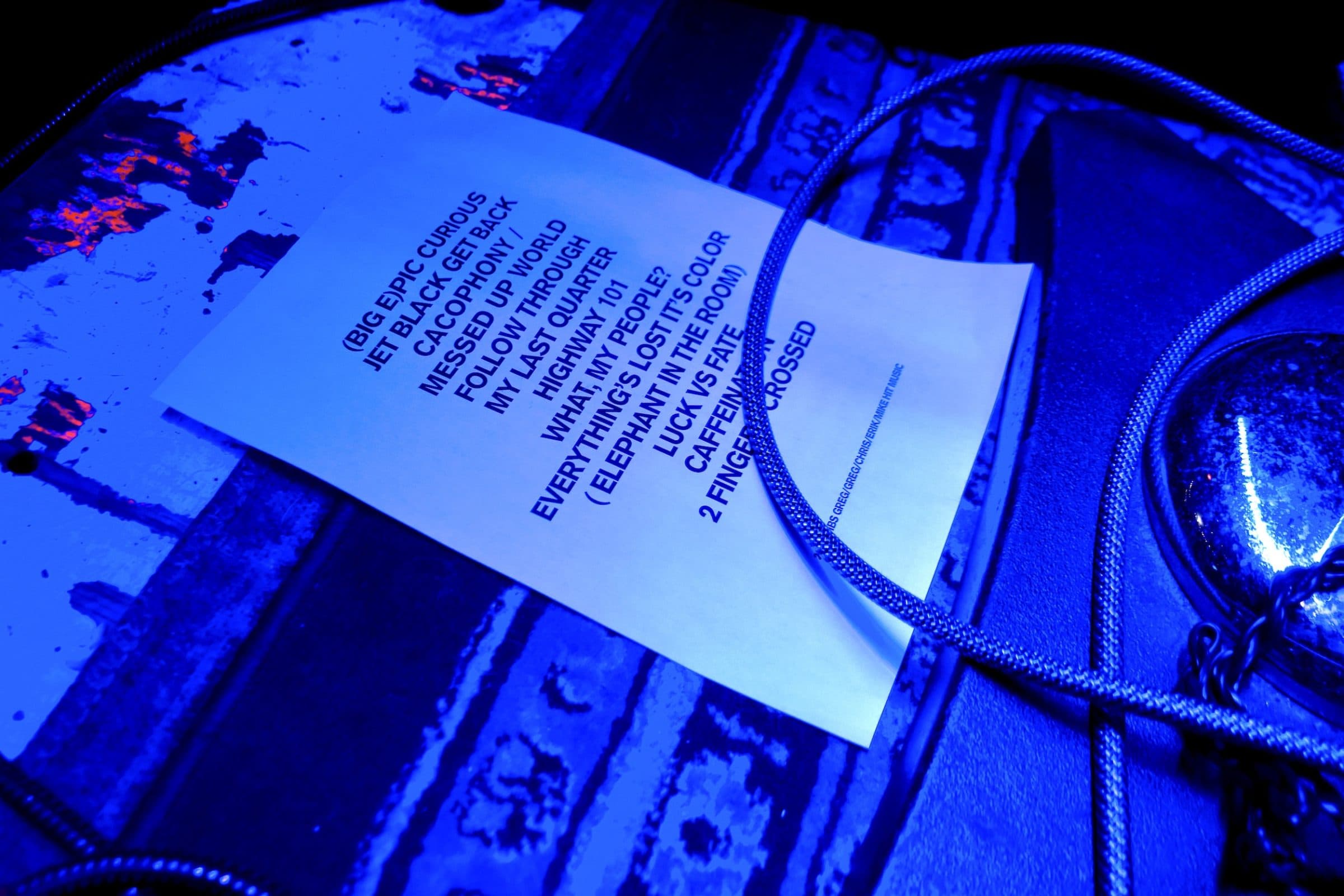

GH: I think I’m gonna do a bunch of singles off this record. Like, take a whole year and just play shows around it, because I really like it. It still feels fresh—I haven’t gotten bored with it yet. We’re already playing three songs off it live, and they’ve made it into the set. And with the horn section in the mix now, I’d love to explore more of the songs in that format.

The only problem is, you usually get 45 or 50 minutes, and you’ve gotta hit the ones people know, the ones you’ve been playing for, in some cases, 20 years. So it’s always a balance. But yeah, I’m leaning into this record for a while.

As far as new stuff… I’m in the middle of a move to Colorado, which is great—but it also means my studio is in boxes. So the one commitment I’ve made is not to record anything for a bit. Just enjoy this season. I can get so caught up in the process that I move on too quickly—before the music’s had a chance to find its audience or to breathe out in the world. I want to give this one time.

That said, I have been working on a little side thing. A really good friend of mine, Maria (Xeno)—she’s in this amazing hardcore band called Humanhead out of San Jose—I saw them at Kilowatt the other night. She’s an unreal scream singer. Anyway, she and I have been collaborating on this kind of trip-hop project, on and off. We’ve probably got five songs demoed. It’s darker, kind of moody—closer to Portishead or Tricky than De La Soul, but yeah, it has that 90s flavor. Lots of dark beats. I’ve been playing with drum loops, making them sound like machines, and layering in synths and keys. It’s been fun. We even have a name, though I won’t say it yet—it might not stick.

Our hope is to eventually play two-person shows that are super visual—lots of lights, maybe video—where it’s all sequenced and stripped down. Like, I’d play keys, and she’d just sing. It’s kind of the total opposite of what we each do live right now, which is usually high-energy, loud, chaotic. So this would be a cool contrast.

And yeah, I always love taking breaks to make instrumental electronic stuff, especially now while everything’s packed up. I’ll probably end up sitting at my computer messing with soft synths, just to feel like I’m still creating something while the studio is out of commission.

But moving is huge. We’re moving the whole family from San Francisco to Boulder. It’s gonna be a big shift, and I want to let myself live in that for a while. You’ve moved before—you know it takes a lot out of you.

After this call, I’m hopping on the phone with my Midwest booker to plan some dates around Colorado. I’ve played a bit there before, but it’s such a musical state. There are great little roadside venues, cool mountain towns, ski area gigs—it’s a scene I’d love to dig into more. Especially now with the horn section, I feel like we can really stretch the sound. I was brushing my teeth the other day and thought, “We could totally cover Play That Funky Music, White Boy.”

WW: You could! I literally heard that on the radio yesterday!

GH: Right? It fits the live vibe we’re in right now. You’ve gotta throw a cover in during those two-hour sets.

But yeah, I do think moving changes your perspective. I’m trying to be really aware of that. Not rushing into new material. If inspiration comes, I’ll just sit with it. Maybe I’ll pick up the acoustic and write the old-school way.

Oh, and I’ve got this whole other record I made back in 2021. Me and two close friends spent a week in a little cabin up near Duluth, Minnesota. We tracked the whole thing live—pretty much live—and it came out great. And I still haven’t gone back to it.

WW: Wait, really? So there’s another whole album out there?

GH: Yep. Still unreleased. There’s like twelve songs. Every time I listen back, I’m like—okay—this is way better than I remember.

We were up there barbecuing and drinking bourbon—it was a whole man’s man week. And I think I realized there’s going to be other opportunities for me to work with stuff without having to sit down and reinvent the wheel every time.

WW: Because you’re moving away from it, can you reflect on what the Bay Area music scene has meant, and what you’re leaving behind?

GH: Okay, so I think I should preface this by saying I lived in New York City for 12 years before I got out here.

It’s hard to decouple that era from what the city was then. And when I got here—out west—so much was already changing. Phones, the internet, how people find entertainment. San Francisco has had some ups and downs when it comes to live music. And of course, we all had the pandemic. That’s its own thing.

For a while, it really felt like everything was happening in Oakland. I was going to Eli’s, The Stork Club—all these phenomenal places over there. And when I try to put it all in retrospect, I think I’ve seen three distinct periods in the Bay Area over the past 15 years.

The first is when I arrived. It was pretty great. It took me about two years to form a band. We were playing Thee Parkside, El Rio, The Knockout… all these great smaller 50-60 capacity rooms. It was popping.

The second is right before the pandemic—around 2017 or 2018. Suddenly you had Lyft and Uber. People had more access to go out—but they started going out less. Live music started to take a back seat to DJ nights and dance stuff. Maybe that’s just the Bay Area, I don’t know, but it felt like a real shift in what people were willing to spend time and money on.

I think 2020 really kind of screwed everybody up in the live industry.

WW: Sure.

GH: And I think that a lot of clubs now are still trying to get their footing around this business model—how to get people back.

WW: I think you’re right.

GH: I’ve given a lot of direct feedback. I gave direct feedback to a club in New York on this last tour, and they didn’t even write me back. I think he was pissed off at me because I said, “Listen, I think you’re doing this in a way that is not congruent with what people want right now.” And I think that’s, you know—we played Kilowatt from one to five with Fuzz Kit and DAIZY and . Free show. Amazing.

It was Greg Hoy and the Boys West–Greg Reeves on bass, Chris Cookies Kelly on drums, Erik Hoagland on sax, and Mike Sanchez on trumpet.

How great to just tell people to just show up on a Saturday afternoon to see live music? And we were doing that at Bottom of the Hill. I was sponsoring the Sunday barbecues for a while before Mike passed away. And I find, you know, getting people out of the house earlier—and I don’t think this is just an age thing—I literally think people don’t want to stay out drinking all the time anymore.

And I think the clubs that are adapting outside of that—outside of the idea of people want to, like, start watching live music at nine o’clock until one in the morning, and you’re going to have, like, this—you know, a bunch of people that are sitting around doing shots and drinking your beers and all that stuff—I think it’s all kind of part of this bigger kind of sea change that I’ve seen since I’ve been here.

WW: Because I have an alcohol client and I follow the industry, I’ve seen statistics that say people have reduced their consumption, and overall the younger generations—whatever letters or numbers that you want to give to them—are fundamentally drinking less.

And that probably coincides with, “I don’t want to stay out until four in the morning or two in the morning.”

GH: And it’s not that people don’t want to sort of be in person with other people. It’s just you have to do it in a way that gives them—gives their endorphins—what they’re looking for. And I think, you know, having more day shows, having more free shows, figuring out different ways to monetize why people are getting together versus just to drink—I think this is all really important for the survival and success of the live music industry.

WW: I’ve been wondering about clubs—literally—getting back to being clubs. What I mean is, “Hey, you can be a member of Winters Tavern.” And instead of paying a fee at the door, you’re gonna pay a monthly membership to Winters Tavern—you can come anytime. You don’t have to worry about, “Is there a cover tonight?”

I wonder if venues need to experiment with other types of business models.

GH: And I think that’s what needs to happen. We need to crack open the old business model. Because you still have club owners who say, “Bands aren’t bringing in enough people.” And then bands are like, “You’re not promoting.”

WW: Right.

GH: We all want the same result here.

WW: And I could understand why someone would say, “That’s risky too, William. Interesting idea. What if it doesn’t work, and now I’ve now sold a grand total of three memberships?”

Greg: Your venue needs to be something—it needs to be a brand. It needs to be top of mind. Like, two marketing guys talking here, but… when someone says, “Where should we go tonight?” you want your place to pop into their head.

There’s this band I love called Hillbilly Casino—they’re from Nashville. I caught them one night at one of the Broadway clubs, and then the next night they were playing this supper club. William, it was so good. The stage looked like something out of the ’50s—well lit, super classic. The audience was sitting at tables, getting table service, eating dinner, having drinks. And the band wasn’t so loud that they overwhelmed the room. Their hardcore fans were seated up front, close to the stage, which was perfect.

That night was packed, and you could just tell everyone had a great time. The music was part of this bigger social experience—eating, drinking, being out in the world. There was no FOMO, no urge to leave and see what else was going on. You just knew you were in the right place, at the right time. That’s the magic you want to create.

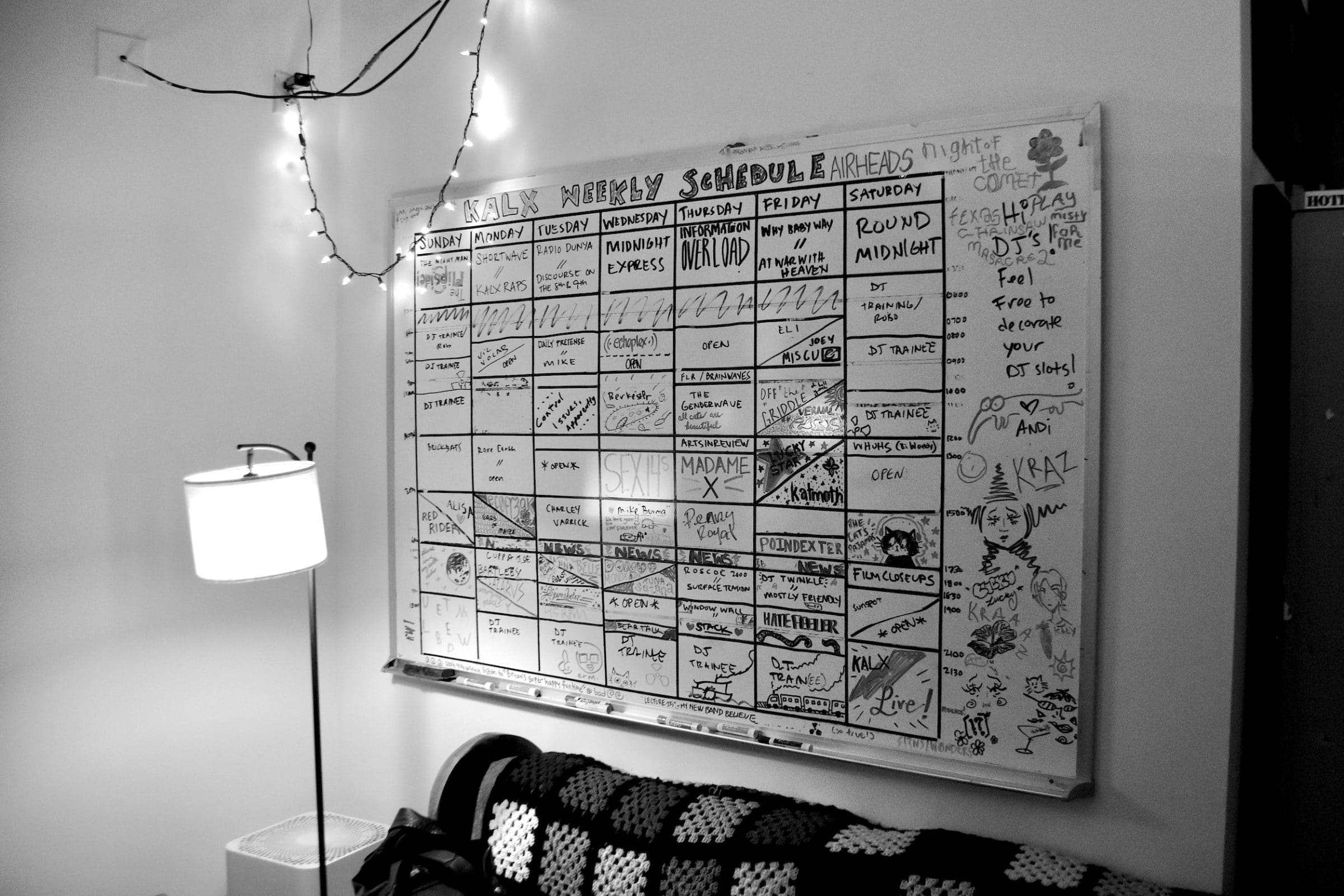

WW: I love that. OK, I want to shift gears a bit. You mentioned your publicist earlier, and I want to talk about that. One thing I’ve always thought about you, Greg, is that you’re just a natural promoter. I think it’s a real skill. How did the interview with Polly Vinyl at KALX come about? And more generally, how do you approach PR?

Greg: I think it’s all about taking what you have and using it to the fullest. When I started getting back into music in earnest—this was around 2019, right before the pandemic—I realized that there are all these tools available: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter at the time. And I thought, OK, what’s the story I’m telling here?

A lot of people skip that step. But to me, it was like—figure out your story first. For me, the story became trying to be the most authentic version of myself. That sounds cheesy or woo-woo, but I spent years in bands where we’d be like, “OK, let’s put on eyeliner, let’s wear our Hot Topic jeans”—which, by the way, I still wear because they fit really well! [Laughs] But back then, we were trying stuff on, you know?

That used to work. But now I think it’s kind of the opposite. The more I lean into just being genuinely myself—curious about people, empathetic, constantly exploring new music—the more real it feels, and the more people respond to it.

I’ll go to the Ivy Room website or Bottom of the Hill, and just scroll through the bands. If there’s one I’ve never heard, I’ll look them up on Spotify or YouTube and check them out. That comes from a selfish place, in a way—this is what I do, and I want to see how other people are doing it.

WW: I don’t think that’s selfish at all.

Greg: Right, and I guess I mean “selfish” in a good way. I think that word gets a bad rap. But when you come from a place of curiosity and empathy, life just feels more alive. Conversations like this—talking about music and life and how it all fits together—that’s the stuff I live for.

Like with KALX, just walking into that radio station… it’s still there. There’s a room full of records, all that history. And you can feel it, you know? It’s not just a place where someone gets on the mic and spins songs. There’s decades of culture baked into the walls. That’s powerful.

WW: I just have to say—the whiteboard with the schedule, the old-school desks—yes! And the whole record room. I should have asked to explore the record room a little more. And then the studio booth, with the turntables—it was great. I loved that place.

GH: Yeah, and similarly, when we’re on tour, I want to talk to the owner. It’s like the opposite of “I want to speak to the manager.” It’s “Get me the owner.” I want to hear the history. Why’d you buy this place? What’s your story? That curiosity—

WW: That’s just always been in you.

GH: Exactly. And I think it makes me a better person. A better artist. A better human. I love that. That’s what gets me out of bed in the morning. It’s not a paycheck—I’ll tell you that.

WW: Does that kind of thing get you more interviews? Like this one, or radio stuff?

GH: I’d like to think so. I think you and I are rare. Our Venn diagram has a lot of overlap. I’ve done interviews where it’s a totally different vibe. Like, a couple years ago, I did one with a woman who had a podcast centered around artists and abusive relationships.

WW: Wow.

GH: Yeah. That was a big moment for me. I’ve been in an abusive relationship. And I had to ask myself—do I want to bring this into Greg Hoy the musician? Do I really want to post something like, “Hey everyone, check out this podcast where I talk about abusive relationships”? That’s a decision.

But I think those are the moments—when you’re up against something—that’s when the real stuff comes out. When you’re forced to ask, “Why am I doing this if not to relate to people on a real human level?” Because otherwise, why bother?

So yeah, I want to do that kind of stuff. That’s the reason we’re here—to help each other, to support each other. And the more I let myself fall into that, the more I can let go of the Gen X angst. The darkness we grew up with. The latchkey kid stuff. Watching the Challenger explode on TV because school was canceled due to snow in Pennsylvania.

Getting away from that kind of innate cynicism—it becomes its own reward.

WW: Earlier we were kind of ragging on social media a bit—but then you’ve got artists like Taylor Swift, right? She’s relatively vulnerable online. She lets that happen. And I think we’re in an era where it’s more okay to just be yourself as a performer.

GH: Yeah. You don’t have to adopt a whole David Bowie persona. And when people do that now, unless it’s super over-the-top, it almost feels… icky.

WW: If they’re upfront about it—like, “Hey, this is my stage character”—that’s cool.

GH: Yeah, exactly. Like Kesha, or Gwar, right? Totally different vibes, but both have authenticity.

WW: Right. There’s something real about saying, “This is a performance.” Like an opera or a play.

GH: Totally. When I get on stage, there’s a persona there—but it’s just an exaggerated version of myself. It’s still me. But also, it’s every performer I’ve ever seen. It’s Eddie Spaghetti. It’s Lemmy from Motörhead. It’s David Lee Roth. It’s big. It’s crude. It’s a show.

But if I didn’t do it as myself, it wouldn’t feel real. And if it’s not real, then what’s the point?

WW: Exactly. Who wants to see that?

And on the flip side, you know, I’ve seen musicians whose idea of a performance is just… playing. Playing their instrument, singing the song.

Maybe you’re a great musician, but if it’s not a performance…

GH: Yeah. People can check out. Every time I get on stage, I think—I want to make this worth someone’s time. That’s all I want. I don’t want to be another forgettable act.

Maybe it’s age, maybe it’s just where we are. But now it’s about quality. Making it worth people’s time. And mine.

I think the hardest part, especially on tour, is—you book these months in advance, and then you show up and it’s like…

WW: What do you do when you’re just not feeling it on the road?

GH: You know, you’re in the middle of a tour—say, you’re in Philadelphia for a show—and it’s like, Hey, you don’t want to play that night. Maybe you’ve got a cold, maybe something’s going on emotionally, maybe you just had a fight with your old lady or whatever. You have to take all of that and either use it, or push it aside. One or the other. Because the people that are there? They showed up. They don’t know what you’re going through—and they don’t need to. They came for a show.

WW: Has your mindset about that changed over time?

GH: It really shifted when I stopped performing under band names and just started using my own name. That changed everything. I remember thinking, Cool, now you really have to step up. You have to show up and be a version of yourself that is true. Like, David Bowie was amazing, but even he wasn’t performing under his real name. You know what I mean?

WW: That’s true—“Greg Hoy” is literally your birth name.

GH: That’s the name on my birth certificate. So for better or worse, that’s it. That’s the name my whole ancestry led to. I’ve got to honor that. I’ve got to step up and say, Okay, cool. I’m gonna do it. That’s my job.

WW: Well, that feels like the perfect place to end this.

GH: [Laughs] Yeah, I hear that. This has been awesome. Thank you.

Planning to record? If you’d like to be considered for a future Studio to Stage feature, reach out to William Wayland.

Leave a reply